By Danika McClure

Women have made significant progress in today’s political sphere. Just last year, Hillary Clinton became the first woman in U.S. history to win a major party nomination. This progress is significant, especially when you consider the United State’s precarious history of women’s rights.

Photo courtesy of Google, under creative commons license

Just under a century ago, women in the U.S. fought diligently for their right to vote —— meaning that there are some women alive today who remember what conditions were like before this change. As one author from the Central Asia Institute writes, “[These women] will always think about the struggle, danger and violence women endured to secure that right.” Many faced intimidation tactics, threats of violence, and some were consequently killed trying to use their newfound freedom.

Women have since become a powerful voting demographic but continue to be vastly underrepresented in leadership positions in the government. Women make up only 19 percent of all members of Congress, less than 25 percent of all state legislators, and 12 percent of the nation’s 50 governors, and none have yet served as President.

To put that into perspective, even the clergy has more gender representation than the government at 20.6 percent.

“There's some real perspective [there]," Danielle Kurtzleben tells NPR. "For one thing, a substantial chunk of the clergy has to be men. Several large American religious denominations, including Roman Catholicism, which accounts for one in five U.S. adults, for the most part do not allow women to be ordained. Lawmaking, of course, has no such restrictions, but Congress' women's share is still stuck where it is among clergy."

Our country’s rank for women’s political representation is 78th in the world, according to recent reports, and shows signs of worsening as the political ambition gap between the genders has only continued to widen. But why is this?

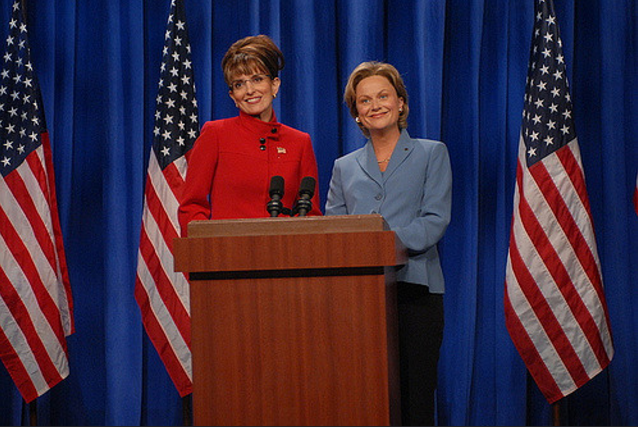

Photo courtesy of NPR

Americans have warmed up to the potential idea of having a female president, which is a drastic change from decades previous. In the 1960s, Gallup polls indicated that only 50 percent of Americans indicated that they would consider voting for a female president. In 2015, 92 percent of respondents indicated that they would vote for a female candidate from their party so long as she was generally well-qualified to hold the position.

The problem also doesn’t stem from a lack of opportunities for qualified individuals. In fact, career opportunities for those in public service are vast. And if we’ve learned anything from recent events, job experience and qualifications aren’t necessarily a precursor for obtaining government positions.

The issue, it seems, is that not enough women are putting themselves out there to obtain these leadership positions in the first place. A study performed by Jennifer L. Lawless and Richard L. Fox titled Men Rule: The Continued Under-Representation of Women in U.S. Politics highlights this particular phenomenon.

Photo courtesy of Google, under creative commons license

Lawless and Fox argue that there are seven main barriers that women in the U.S. face when contemplating a career in public service, especially those in high level government positions. They conclude that

Women are substantially more likely than men to perceive the electoral environment as competitive and biased against female candidates

Hillary Clinton and Sarah Palin’s candidacies shaped the way women perceive gender bias in the electoral arena

Women believe themselves to be under-qualified or less qualified than men to run for office

Female candidates tend to be less competitive, less confident, and more risk averse than males who run for office

Women react more negatively than men to many aspects of campaigning

Women are less likely than men to receive confirmation that they should run for office

Women are by and large still responsible for the majority of childcare and household tasks

There’s evidence of this regardless of party affiliation. In 2014, many female public officials told NPR’s Tamara Keith that they had to be urged multiple times before taking the steps necessary to hold political office.

Photo courtesy of Flickr, under creative commons license

“You need to be asked,” Indiana Lieutenant Governor Sue Ellsperman told Keith. “Women are still not likely to take that first step on their own.”

Likewise, the lack of women’s representation only further exacerbates the problem. If women don’t see themselves in leadership positions they are less likely to run for office themselves. In what has been coined as the “woman effect,” many have found that electing a woman to a major office later results in a 2 to 3 percent increase in women’s representation in the next election cycle.

Unsurprisingly there’s also a difference in women’s representation based on party affiliation. On the whole, women are more likely to run for and earn high level positions as Democrats than they are as Republicans.

"A root cause of the gap is that Democratic women who are potential congressional candidates tend to fit comfortably with the liberal ideology of their party's primary voters, while many potential female Republican candidates do not adhere to the conservative ideology of their primary voters," New York Times author Derek Willis wrote.

Despite all of this, Congress is perhaps the most diverse it’s ever been, and the interest in women running for office has also greatly spiked.

“Since the end of America’s recent presidential election, the number of people expressing interest in running for public office has sharply increased,” according to experts at Rutgers University’s Masters in Public Administration program. In fact, “Emily’s List, a political action committee that helps Democratic, pro-choice women get elected, received over 4,000 inquiries from women seeking assistance running for office. Nearly half of these requests — 1,660, to be exact — were received since January 20th.”

While these numbers are encouraging, it’s too early to tell how voting outcomes will affect women’s future in government positions. And while women have made impressive strides over the past century as voters and as leaders, addressing the root cause of women’s hesitation to run for office is integral to solving the problem.

Bio: